“My Visit to Russia”: Clementine Churchill’s Wartime Travelogue

“My Visit to Russia” is excerpted from an article for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the unabridged text including endnotes, please click here. Subscriptions to this site are free. You will receive regular notices of new posts as published. Just fill out SUBSCRIBE AND FOLLOW (at right). Your email address will remain a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

✸ ✸ ✸

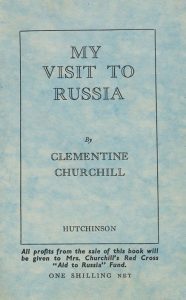

My Visit to Russia is the only book by Clementine Churchill, It was published to support the Aid to Russia Fund, of which Clementine was chairman (the word was gender-neutral in those days). Moya Poezdka V SSSR, a Russian limited edition, was also published. Unlike the pulpy paperback, it was printed on high quality coated paper, but comprised only 20 pages. The Russian text was abridged from the English edition.

My Visit to Russia is the only book by Clementine Churchill, It was published to support the Aid to Russia Fund, of which Clementine was chairman (the word was gender-neutral in those days). Moya Poezdka V SSSR, a Russian limited edition, was also published. Unlike the pulpy paperback, it was printed on high quality coated paper, but comprised only 20 pages. The Russian text was abridged from the English edition.

Aid to Russia Fund

The Aid to Russia Fund began in 1941 after Hitler’s invasion of Russia. It was founded by the Joint War Organisation, under the British Red Cross and Order of St. John of Jerusalem. Its object was to provide Russians with medical supplies during Germany’s invasion and partial occupation of the USSR. Quickly, £1 million was raised, and reached £8 million by war’s end. The fund provided X-ray units and ambulances, along with containers of blankets, clothes and medicine.

Clementine Churchill was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour and the Distinguished Red Cross Service Badge for her efforts. In 1946 she was appointed Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) though she never affected the title. Clementine was generally unconscious of such honors. As her husband cracked in 1953, when he became a Knight of the Garter (KG): “Now Clemmie will have to be a lady at last.”

My Visit to Russia

To thank Mrs. Churchill, the Soviets invited her to tour Russian health facilities which had benefitted from the Fund. She was accompanied by Red Cross Russian Aid Committee secretary Mabel Johnson and her own secretary, Grace Hamblin. Fate took her from Winston’s side during climactic events: the stark horror as the Allies found the Nazi concentration camps; the deaths of Roosevelt, Hitler and Mussolini; the near-death of Winston’s brother Jack; the German surrender; VE Day; the looming break-up of the Churchill coalition government.

Clementine arrived in Moscow on 2 April 1945, with Soviet intentions toward Eastern Europe plainly threatening. Her daughter wrote: “Winston had had very real qualms about the wisdom of letting Clementine go to Russia. However, her visit afforded a welcome opportunity for smiles, not scowls.” She was met by former Soviet Ambassador to Britain Ivan and Mrs. Maisky and British Ambassador Sir Archibald Clark Kerr. “Lovely accounts of your speech and reception,” cabled Winston. “At the moment you are the one bright spot in Anglo-Russian relations.”

Hugging the bear

Early in her visit, Clementine was received by Stalin in the Kremlin. The account in My Visit was suitably diplomatic: “The great warrior leader…was exceedingly kind and gracious in his references to the Aid to Russia Fund.” Stalin said her help “has been on a considerable scale. We are grateful for it.”

Clementine presented Stalin with a gold fountain pen, Winston’s gift, a souvenir of their wartime meetings. “My husband wishes me to express the hope that you will write him many friendly messages with it,” she said. “The Marshal accepted it with a genial smile.” She did not include his words, which she related later to her daughter: “I only write with a pencil.”

Despite Winston’s entreaties, her messages, even in cypher, made few other references to Stalin. He would write few friendly letters in future.

Smiles amid devastation

Clementine covered vast territory, from Leningrad to Stalingrad, Rostov-on-Don to Odessa. My Visit is replete with moving descriptions of war’s effects on the country. She did regard Leningrad as “the most beautiful city I have ever seen,”7 but Leningrad had avoided occupation. En route to Stalingrad she wrote:

What an appalling scene of destruction met our eyes. My first thought was, how like the centre of Coventry or the devastation around St. Paul’s, except that here the havoc and obliteration seems to spread out endlessly…. The Nazis spread death on all sides. It was a policy of deliberate annihilation. But Russia lives!—And the marvelous tenderness and attention given to the tiny babies struck me as a symbol of the Life Force repairing the ravages of war.

My Visit sympathetically describes the brave Russian children who had survived to smile up at her with soft brown eyes, or share a small toy. Russian children were “attractive and charming to look at,” she wrote, and here was a nod to pre-Soviet Russia:

There is some quality in their upbringing that seems to instill obedience and good manners without fear—at least until the age of seven or eight. I believe that no child is ever beaten in Russia. That was true in the old pre-revolution days as well as in Soviet times.

The rush of events

Farther west, events piled up. Winston was now seriously worried about Roosevelt. “My poor friend is very much alone,” he wrote Clementine,

and bereft of much of his vigour. Most of the telegrams I get from him are clearly the works of others around him. However yesterday he came through [with] a flash of his old fire, and is about the hottest thing I have seen so far in diplomatic intercourse…. [M]uch of this stuff is dynamite….Well you know how great our difficulties are about Poland, Rumania, and this other row about alleged negotiations. I intend still to persevere, but it is very difficult.

These frank exchanges ceased after Clementine left Moscow. Without the benefit of the cypher code through the British Embassy, their letters were necessarily circumspect. She did pass through Moscow on 13 April, en route to Stalingrad, where she learned of Roosevelt’s death the day before. There she had a brief telephone conversation with her husband. His note the next day gives the lie to assertions that he deliberately snubbed FDR’s funeral: “At the last moment I decided not to fly to Roosevelt’s funeral on account of much that was going on here.”

M. Herriot on VE-Day, 8 May 1945

At the British Embassy with Clementine to hear Winston’s VE-Day address was Édouard Herriot, recently freed from a German prison. A French radical, Herriot had been prime minister, and had been President of the Chamber of Deputies in 1940. As such he had been present at Churchill’s last 1940 visit to France, when WSC tried to rally the despairing government.

Adamantly opposed to Vichy, Herriot was arrested and imprisoned in Germany. As they listened to Winston’s broadcast he said to Clementine:

I am afraid you may think it unmanly of me to weep. But I have just heard Mr. Churchill’s voice. The last time I had heard his voice was on that day in Tours in 1940 when he implored the French Government to hold firm and continue the struggle. His noble words of leadership that day were unavailing. When we heard the French Government’s answer, and knew they meant to give up the fight, tears streamed down Mr. Churchill’s face. So you will understand that if I weep today, I do not feel unmanned.

A souvenir of sterner days

Despite its modest appearance, My Visit to Russia is worth seeking out. Clementine Churchill’s dramatic word-pictures of Russia’s devastation remind us of Winston’s words to her about war: “I feel more deeply every year—and can measure the feeling here in the midst of arms—what vile and wicked folly and barbarism it all is.”