El-Sisi: The Churchill Test; Another Damaskinos?

“El-Sisi: The Churchill Test” was written 2014. It’s 2023, and he’s still there. Hmm.

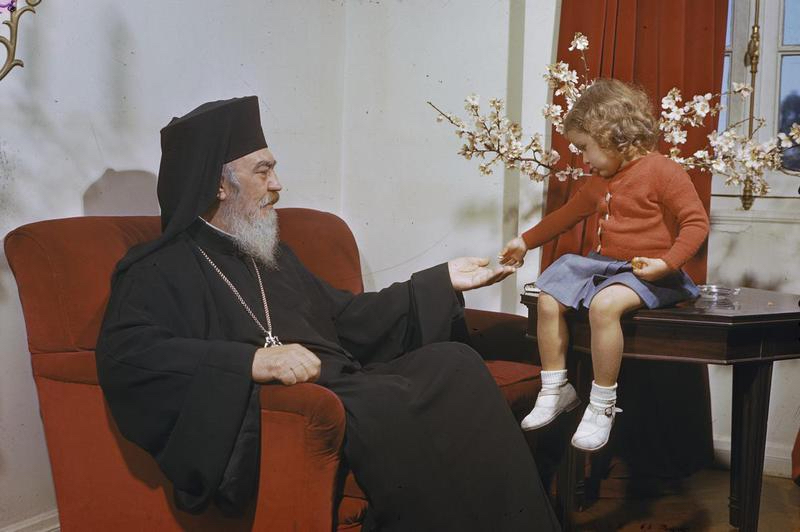

Damaskinos, 1944

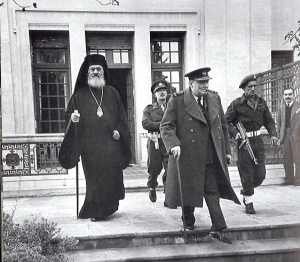

On Christmas eve 1944, Prime Minister Winston Churchill left family celebrations and flew to Athens. He hoped to mediate the Greek civil war. Communists and royalists were fighting it out. Armed with one promise Josef Stalin actually kept, Churchill thought he could give peace a chance.

(Stalin’s kept promise was the roundly-condemned “percentages agreement” in Moscow a few weeks earlier. It gave Britain a sphere of influence in Greece in exchange for Soviet spheres in pretty much the rest of Eastern Europe.)

Churchill had never heard of Archbishop Damaskinos, the man his Foreign Office said might reconcile the factions and head off a Communist takeover. In Athens, Churchill fixed a steely eye on the general commanding British troops:

“This Damaskinos—is he a man of God, or a scheming prelate more interested in temporal power than the life hereafter?”

The general replied, “I think rather the latter, Prime Minister.”

“Good,” Churchill replied: “That’s our man.”

Schemer or saint?

The general’s was a harsh judgment. During the war, Damaskinos had issued Christian baptism certificates to Jews fleeing the Nazis, becoming one of the “Righteous Gentiles” during the Holocaust; but he was certainly ready to take and exercise power.

In Piraeus harbor the towering Archbishop was piped aboard HMS Ajax to meet Churchill. It was Christmas day: sailors were celebrating, dressed as goblins, gypsies and hula dancers, occasionally throwing one of their number overboard. The Archbishop, in clerical robes with a headdress that made him even taller, seemed a fellow celebrant. Sailors advanced with every intent of tossing him over the side. They were dissuaded with difficulty, as the captain convinced the priest that it was not a staged insult.

At a conference in the Greek Foreign Office, lit only by hurricane lamps as bombs burst over the Piraeus, Churchill subjected the warring Greeks to a discourse the like of which they had never heard before. The two factions agreed to appoint Damaskinos as Regent; he called for reconciliation, ended the fighting, and left office in 1946 with Greece a constitutional monarchy.

El-Sisi, 2014

Flash forward 70 years almost to the day for another Mediterranean schemer: Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi—no man of God, and likewise no sissy.

In October 2014, after attacks by jihadists in northeast Sinai, el-Sisi bolstered his forces. He routed Hamas insurgents and destroyed tunnels by which arms were smuggled in from Gaza. Then he closed Egypt’s borders to a Hamas delegation, accusing Hamas of engineering violence. Hamas’ attempts to placate Cairo after a long estrangement collapsed. Hoping to curry el-Sisi’s favor, Hamas even severed its ties with the Muslim Brotherhood.

You remember the Muslim Brotherhood—those “reformers” the West backed during the “Arab Spring.” After an election in June 2012, the Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s president. Alas Mr. Morsi was no sooner in office than he morphed from Jeffersonian democrat to a tyrant, and was deposed by el-Sisi and the Army a year later.

El-Sisi’s coup was protested by those who welcome any leader who is elected, even if an election is not exactly up to the standard of, say, the League of Women Voters. They called for stopping aid to Cairo, presumably until Egypt got back to electing another Morsi. El-Sisi ignored all that, and his determined actions against the jihadists offer a chance to stabilize Sinai. That may take him years, not to mention pacifying other trouble spots deeper inside Egypt.

Idealism and Realpolitik

Recently, author David French suggested that idealism will be the death of us—be it President Bush’s faith in democratic nation-building, or President Obama’s arming of unpredictable zealots: “We have to replace foolish hopes and deadly dreams with hard-nosed evaluations of action. Allies such as the Kurds have proven themselves reliable time and again, and Egypt’s new government has shown promise in its treatment of Hamas.” We seem, French writes, “more willing to arm jihadists in Syria than to arm the Kurdish peshmerga in Iraq.”

History doesn’t repeat, Mark Twain said, but it sometimes rhymes. In Athens 70 years ago, a hard-nosed Churchill saved Greece with realpolitik and a tough-minded leader who stifled the forces of anarchy. The situation is not the same today. The opportunity is eerily similar. Churchill said late in life:

The Middle East is one of the hardest-hearted areas in the world. It has always been fought over, and peace has only reigned when a major power has established firm influence and shown that it would maintain its will. Your friends must be supported with every vigour and if necessary they must be avenged. Force, or perhaps force and bribery, are the only things that will be respected. It is very sad, but we had all better recognise it. At present our friendship is not valued, and our enmity is not feared.