Churchill and George Bernard Shaw: Less than Meets the Eye

“Churchill and Shaw” is excerpted and condensed from my “Great Contemporaries” article for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete text please click here. (Subscribe to regular Hillsdale Churchill posts by scrolling to the bottom of any page to “Stay in touch with us” and filling in your email.)

“Loud cheers rent the welkin”

Winston Churchill was not a hater, with the singular exception of Hitler—“and that,” as he said, “is professional.” Churchill also loved the theatre, and ipso facto the plays of George Bernard Shaw. Shaw was a left-wing polemicist who in 1931 visited and praised Stalin’s Russia. Churchill laughed off Shaw’s politics while acknowledging his literary genius.

Shaw was as enthusiastic about the Soviet Union as Churchill was censorious. Churchill compared Lenin to a typhoid bacillus; Shaw called him “the one really interesting statesman in Europe.” In 1931, Shaw joined a party led by Nancy Astor on a well-publicized Soviet tour. Shaw described Stalin as “a Georgian gentleman.” At a Moscow dinner he declared: “I have seen the ‘terrors’ and I was terribly pleased by them.”

This was too much for Churchill, who despised hypocrisy. Shaw, after all, had made a fortune in capitalist Britain. Shaw, Churchill wrote, was “the world’s most famous intellectual Clown and Pantaloon.” His description of Shaw’s Moscow reception was classic:

The Russians have always been fond of circuses and travelling shows. Since they had imprisoned, shot or starved most of their best comedians, their visitors might fill for a space a noticeable void…. Multitudes of well-drilled demonstrators were served out with their red scarves and flags. The massed bands blared. Loud cheers from sturdy proletarians rent the welkin….

Commissar Litvinoff, unmindful of the food queues in the back-streets, prepared a sumptuous banquet; and arch-Commissar Stalin, “the man of steel,” flung open the closely guarded sanctuaries of the Kremlin and, pushing aside his morning’s budget of death warrants and lettres de cachet, received his guests with smiles of overflowing comradeship.

Exchanges and ripostes

Shaw for his part enjoyed needling Churchill in equable spirit. In 1928 he sent WSC his magnum opus, The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism. In 1934, Shaw wrote to praise Churchill’s Marlborough as “very good reading [but] badly damaged in places by [excess] Macaulayisms.” Cutting back on Macaulay “is easily within your grasp,” he wrote WSC. “And forgive me for meddling; but the book interested me so much I could not keep quiet.”

In 1937, Churchill reprised a 1929 sketch of Shaw in Great Contemporaries, and Shaw apparently enjoyed it. (It is certainly worth the reading today—Churchill at his literary best.) Shaw liked it, but Churchill had described “The Red Flag” (Labour Party hymn) as “the burial march of a monkey.” Not so, Shaw protested. “The Red Flag” was actually “the funeral march of a fried eel.”

An exchange of barbs denied by both sides

We are constantly asked to verify a famous exchange. Shaw writes: “Am reserving two tickets for you for my premiere. Come and bring a friend—if you have one.” Churchill replies: “Impossible to be present for the first performance. Will attend the second—if there is one.”

Though it’s lovely repartee, both of them denied it.

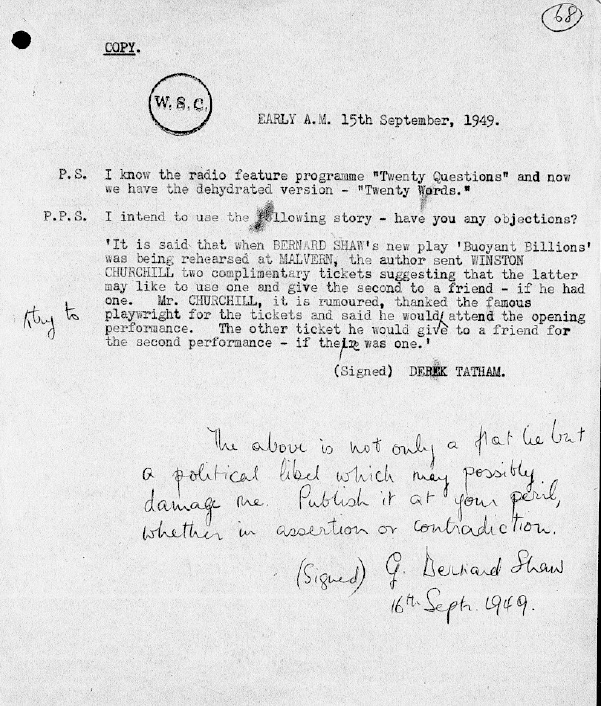

Five years ago Allen Packwood, director of the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge, blew the story apart. In the Churchill Papers he found a set of letters (CHUR 2/165/66,68) in which both Shaw and Churchill denied the exchange. The play in question was “Buoyant Billions” (1948).

Adamant denials

On 15 September 1949 Derek Tatham, representing the London booksellers Alfred Wilson, wrote to Shaw: “Intend to use the following story—have you any objections?” Tatham gave a slightly different version of Churchill’s reply. He says he will attend the opening performance and give the other ticket to a friend for the second performance, “if there was one.”

An outraged Shaw scrawled on Tatham’s enclosure in his own hand: “The above is not only a flat lie but a political libel which may possibly damage me. Publish it at your peril, whether in assertion or contradiction.”

Undaunted, Tatham wrote to Churchill, saying he intended to publish the story, “together with this typical Shavianism, in facsimile,” in a new magazine devoted to books and literary topics. Did Mr. Churchill have any comment?

Churchill’s secretary, Elizabeth Gilliatt, replied emphatically on the 16th: “I am desired by Mr. Churchill…to inform you that he considers Mr. Bernard Shaw is quite right in calling the incident to which you refer ‘a flat lie.’”

We have found nothing further on Derek Tatham (H.D.S.P. Tatham). There is no evidence of the literary magazine he planned ever being published. There is no other contemporary appearance of the Shaw-Churchill exchange. This has not prevented it from being widely accepted for years. A Google search for “bring a friend, if you have one” nets 77,000 hits. We have not searched all 77,000.

3 thoughts on “Churchill and George Bernard Shaw: Less than Meets the Eye”

If Shaw was lying in the initial denial, would Churchill have called him out? I think unlikely.

–

A good point, but Shaw’s emphatic denial, threatening to sue anybody who quoted it, suggests he was fairly determined to claim it never existed. Lacking any further proof, we have to take them at their word. -RML

I feel your pain. I’ve dined out on that one a score of times. Here’s what to do. Say they both hotly denied it, but if it isn’t true it is so much in character for them both that it ought to be.

I believe this exchange. It has always seemed totally in character—- denial just reinforces it. What proof do I have? None! I like it too much to give it up. If we believed every denial by notables— “I was quoted out of context” for example— we would be left with no public and controversial statements by politicians.

Comments are closed.