Why Churchill Skipped the Roosevelt Funeral in 1945

Excerpted from “Dudgeon or Duty?: Churchill’s Absence from the Roosevelt Funeral,” my essay for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. To read the original article with endnotes, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from the Churchill Project, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

The funeral quandary

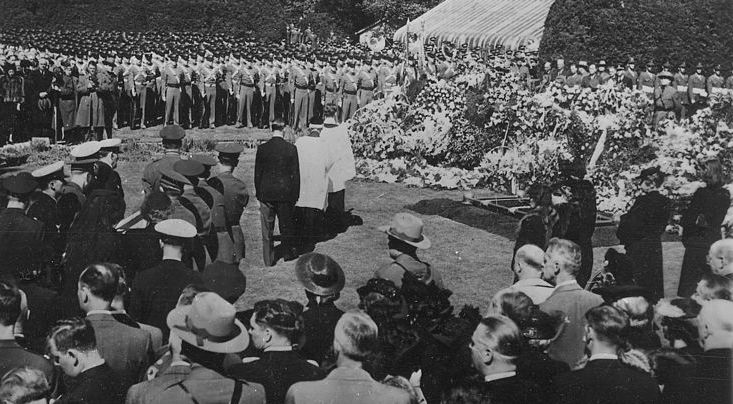

President Franklin Roosevelt died on 12 April 1945 and his funeral ceremonies began two days later. A reader asks why Churchill was absent: “A number of sources, some reputable historians, say he purposely skipped the funeral out of strategy or personal feelings. Is there any truth to these assertions?”

There is conjecture that Churchill missed the funeral for political reasons, or envy at FDR’s position as de facto Allied leader. There is also considerable evidence to the contrary. Defenders argue that his absence was owed to circumstances during a critical time. There may be a broader lesson here, on the difficult choices facing statesmen in fraught times.

Reasons of strategy?

Warren Kimball, editor of the Churchill-Roosevelt Correspondence and erudite works on their wartime relationship, suggests that Churchill’s absence was a political strategy:

Churchill’s decision not to attend Roosevelt’s funeral was an attempt to bring the mountain to Mohammed—subtly to shift the focus of the Anglo-American relationship from Washington to London. “I was tempted during the day to go over for the funeral and begin relations with the new man,” he wrote to the King, but “I should be failing in my duty if I left the House of Commons without my close personal attention….”

This is plausible, considering how Churchill’s presence might have actually drawn attention away from the solemnities. Consider also how little Churchill might have accomplished with Truman during the preoccupying events of the funeral. The new President was facing sudden, enormous challenges. Could they prepare for substantive talks in a day? Churchill’s two 1941 meetings with FDR had been preceded by long sea voyages, full of lengthy planning sessions with his staff.

Artifice and affection?

Jon Meacham, author of the dual study Franklin and Winston (2003) had the impression “that the decision was partly political and partly emotional, the product of a prideful moment in which Churchill, after playing the suitor to Roosevelt, wanted to himself be courted….. Was Churchill, tired of dancing to another man’s tune, relieved Roosevelt was dead? Had it all been an act? No—like so many human relationships, Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s was a mix of the selfish and the unselfish, of artifice and affection.”

One might expect those around the PM, such as Jock Colville or Lord Moran, to mention this possibility in their memoirs. But if there was evidence of Churchill being “tired of the dance.” No intimates suggest it. All we have on record are Churchill’s deep sense of loss, also recorded by Meacham, to Eleanor Roosevelt, Harry Hopkins and Parliament.

A fit of pique?

Less charitable than Kimball or Meacham was the late Christopher Hitchens. He declared that Churchill skipped the funeral in “pique at Roosevelt’s repeated refusals to visit Britain during the war.” Three years later, Richard Holmes adopted a similar line in Footsteps of Churchill (2005):

It is not unreasonable to wonder whether FDR’s death…did not strike Winston as robbing him of the timely finale to which he himself aspired. Nothing he said to those closest to him at the time or wrote later offers a clue to why he chose not to pay his last respects to the man with whom his fate had been so closely bound, and to spurn an invitation to confer with Harry Truman…. Such a flagrant departure from Winston’s normal standards of behaviour, and such a lapse in his duty as prime minister of a nation that needed U.S. good will more than ever, argues that some irrational factor was at work.

First, in April 1945, Churchill was not anticipating his finale. Second, what he said to those closest to him does offer clues to his decision, and these are not irrational. So let us consider the case most likely. It comes, as most sound interpretations do, from the official biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert.

First impulse

Washington ceremonies were set for 14 April, interment at Hyde Park the next day, Sir Martin wrote. “No sooner did he hear the news than Churchill made immediate plans to fly to Hyde Park….

He would leave on 8.30 on the evening of April 13. Everything ready for his departure, but by 7.45 he was unsure. “PM said he would decide at aerodrome,” noted [Alexander] Cadogan in his diary. At the last moment Churchill decided not to go, explaining to the King that with so many Cabinet Ministers already overseas, with Eden on his way to Washington, and with the need for a Parliamentary tribute to Roosevelt, “which clearly it is my business to deliver.” he ought to remain in Britain.

Churchill’s reasoning was confirmed by Anthony Eden, his Foreign Minister, in his own memoirs. Eden was due in America for the United Nations conference—another factor influencing Churchill’s decision.

What we know

There is more evidence backing Gilbert’s and Eden’s scenario, as Paul Courtenay summarized in reviewing Holmes’s book:

Churchill told his wife: “I decided not to fly to Roosevelt’s funeral on account of much that was going on here” (per Mary Soames). He wrote to Harry Hopkins: “…everyone here thought my duty next week lay at home, at a time when so many Ministers are out of the country” (per Martin Gilbert). And: “P.M. of course wanted to go. A[nthony Eden] thought they oughtn’t both to be away together…. P.M. says he’ll go and A. can stay. I told A. that, if P.M. goes, he must…. Churchill deeply regretted in after years that he allowed himself to be persuaded not to go at once to Washington” (per Alexander Cadogan).*

There is no doubt that Churchill faced one of the statesman’s painful decisions. There was, after all, a World War going on, but the Allies were closing on Berlin. The end might come any day. Yet there is no doubt about his bereavement. “I feel a very painful personal loss, quite apart from the ties of public action,” he telegraphed to Harry Hopkins. “I had a true affection for Franklin.”

The reader may decide if there was more to it than that. Was there a subtle, underlying vein of strategy or regret? Even then, Churchill’s decision was not irrational. It is not hard to believe that, with victory approaching, he would wish to be close at hand.

___________

* Paul H. Courtenay, “Greatness Flawed,” in Finest Hour 128, Autumn 2005, 37. Mary Soames, Speaking for Themselves (1998), 526. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. 7, Road to Victory 1942-1945 (2013), 1294. David Dilks, ed. The Diaries of Sir Alexander Cadogan O.M. 1938-1945 (1971), 727.

Churchill’s tribute

Two days after Franklin Roosevelt was interred at Hyde Park, Winston Churchill addressed Parliament:

I conceived an admiration for him as a statesman, a man of affairs, and a war leader. I felt the utmost confidence in his upright, inspiring character and outlook, and a personal regard—affection I must say—for him beyond my power to express today….

In the days of peace he had broadened and stabilized the foundations of American life and union. In war he had raised the strength, might and glory of the Great Republic to a height never attained by any nation in history.… But all this was no more than worldly power and grandeur, had it not been that the causes of human freedom and of social justice, to which so much of his life had been given, added a lustre to this power and pomp and warlike might, a lustre which will long be discernible among men.…

For us, it remains only to say that in Franklin Roosevelt there died the greatest American friend we have ever known, and the greatest champion of freedom who has ever brought help and comfort from the new world to the old.

And to quote again my old friend Professor David Dilks: “If you will allow the remark in parenthesis, ladies and gentlemen, do you not sometimes long for someone at the summit of our public life who can think and write at that level?”

One thought on “Why Churchill Skipped the Roosevelt Funeral in 1945”

Roosevelt humiliated Churchill on two occasions, first in 1941 when the Atlantic Charter was drafted by Roosevelt, which was going to be a disaster to the economic interest of Britain, especially Clause 3 of the Charter. Another occasion was 1943 in Teheran, the first wartime meeting between Big three leaders. Amid the conference, a secret meeting had been held between Stalin and Roosevelt to avoid Churchill. They discussed relinquishment of the British colonies.

–

Thanks for comments. “Humiliated” is kind of strong, but there is no doubt that WSC was extremely disappointed by FDR’s attitude toward the Empire and his private meeting with Stalin at Teheran. But FDR did not press Britain on India. Wikipedia has an accurate account of that: https://bit.ly/3BULG4T.

Nor was Clause 3 very specific. FDR and WSC declared: “They respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.” The last part of that was Churchill. There was plenty of give and take in their relationship, and as Churchill said, “the only thing worse than fighting with allies is fighting without them.” —RML

Comments are closed.