Poland or Russia: Did Churchill Pick the Right Enemy?

Reprinted from “Poland Versus Russia,” written March 2024 for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article (and a spirited exchange with a reader), click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Question: Did Churchill abandon Poland?

The Anglo-Polish Alliance was signed on 25 August 1939 but was tentatively agreed to as early as 31 March 1939: The British would come to Poland’s aid in the event that they were invaded by a foreign power. No country was named. Britain lived up to her agreement with Poland when Germany invaded. However, in about a fortnight after the German invasion, the Soviet Union invaded Poland and the British did nothing. When the Polish Government asked the British Foreign Office for aid against the Soviets, Foreign Minister Halifax responded that the Anglo-Polish alliance was restricted to Germany.

Winston Churchill became the new Prime Minister on 10 May 1940. The Soviets occupied Poland for nearly two years. Churchill had to know the intent of the Communists, and yet he did nothing. On 22 June 1941 Churchill crawled into bed with Stalin. Where was the statesmanship in that? Of course, you know all these things.

Was Churchill’s fight with Hitler a personal one? He knew that Communism was just as evil as Nazism. He had nearly two years to contemplate what to do about Russia. Churchill had several choices. The best choice would have been to let the Soviet Union and Germany slug it out. We are not talking about hindsight because Churchill had a clear choice then, and time to study his options. The Communists had a much longer history of oppression than the Nazis. —W.S. via email

Answer: Poland before the war

Thank-you for your observations, which are best considered in context of the time. Many factors need to be considered here.

Poland owed her independence to the Allied victory in 1918. Yet the 1938 Polish government was hardly a passive neutral, having joined the Germans and Russians in dismembering Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement.

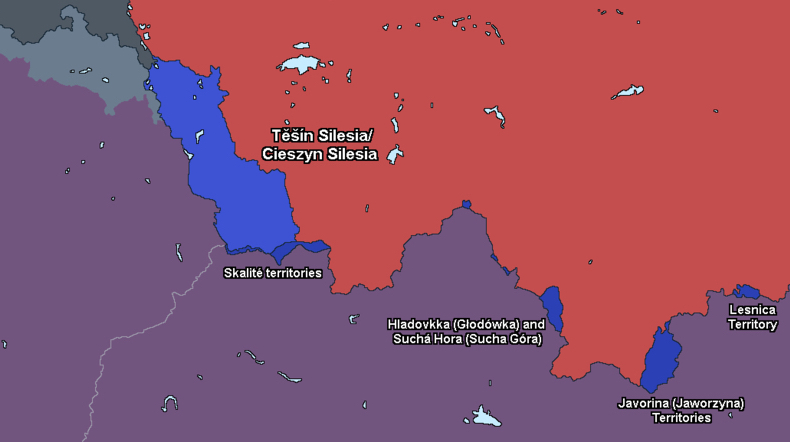

Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck, who admittedly didn’t expect a German assault on his country, took advantage of the Munich affair. Claiming that the Czechs were mistreating their Polish minority, Poland invaded and seized Teschen, a Czech industrial district with 240,000 people, and three other districts. In Parliament, Churchill was furious:

The British and French Ambassadors visited Colonel Beck, or sought to visit him, the Foreign Minister, in order to ask for some mitigation in the harsh measures being pursued against Czechoslovakia about Teschen. The door was shut in their faces.

The French Ambassador was not even granted an audience and the British Ambassador was given a most curt reply by a political director. The whole matter is described in the Polish Press as a political indiscretion committed by those two Powers, and we are today reading of the success of Colonel Beck’s blow.

I am not forgetting, I must say, that it is less than twenty years ago since British and French bayonets rescued Poland from the bondage of a century and a half. I think it is indeed a sorry episode in the history of that country, for whose freedom and rights so many of us have had warm and long sympathy.1

Promises kept

In March 1939, Hitler absorbed what had been left of Czechoslovakia after Munich. Realizing now that Germany would never be appeased, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain issued a British guarantee to Poland. “Here was decision at last,” Churchill wrote, “taken at the worst possible moment and on the least satisfactory ground, which must surely lead to the slaughter of tens of millions of people.”2

When Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Britain kept her promise to declare war on the aggressor. But the ground was indeed unsatisfactory: British chiefs of staff had earlier informed the Poles (who understood) that there was nothing practical they could do on the Western Front without the French, who did nothing. Poland was defeated in a few weeks. By prearrangement with Hitler, Stalin helped himself to his share. The Second World War was on.

Churchill forever blamed Poland for complicity in Hitler’s designs by Beck’s rapaciousness in Czechoslovakia. He repeated his charges in his war memoirs, causing him trouble with exiled Poles, who published pamphlets attacking what they saw as a small matter compared to the depredations of Nazi Germany.3 In the face of such criticism Churchill waxed philosophic: “There are few virtues the Poles do not possess, and few mistakes that they have ever avoided.”4

What we know in hindsight

Did Churchill make the right choice between the Third Reich and Soviet Union? “My thought has always been that Nazism had absolutely no eschatology, and would wither on the vine,” William F. Buckley Jr. once remarked. “Only the life of Hitler kept it going, and I can’t imagine he’d have lasted very long. The Communists hung in there for forty-six years.”5

That is arguably true, but we know this in what Churchill called “the afterlight.” Churchill’s attitude was based on the situation as he saw it at the time.

Until 1939, the Russians had not moved beyond their own territory. Long after Poland had been conquered by the Reich, Churchill remained open to an understanding with Moscow. Even though the Russians and Germans had signed a non-aggression pact, he thought it would ultimately clash with Russian national interests.

“Favourable reference to the Devil”

In the event, Hitler took care of that with his invasion of Russia in June 1941. “If Hitler invaded Hell,” Churchill famously cracked, “I would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.”6

With Russia invaded and America still neutral, Churchill was desperate for allies. It was logical to conclude that Germany not Russia was the greater expansionist threat. No one could see far ahead, yet no one worked harder than he for Poland’s independence after the war. No one more admired the valiant Poles who fought with the Allies from 1940 to D-Day and beyond.

Churchill’s many efforts to secure an independent Poland are on record. Sadly, the war ended with Soviet power spread over Eastern Europe. One Russian who grasped what Churchill was trying to do was Ambassador Ivan Maisky. Our review of his diaries may be of interest.

Endnotes

1 Winston S. Churchill (hereinafter WSC), House of Commons, 5 October 1938, in Robert Rhodes James, ed., Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches 1897-1963, 8 vols. (New York: Bowker, 1974), VI: 6009-10. For Beck’s view of German intentions see Melchior Wańkowicz, Poklęsce. Prószyński i Spółka (Warsaw 2009), 612.

2 WSC, The Gathering Storm (London: Cassell, 1948), 271–72.

3 Studnicki, W., An Open Letter from a Polish Political Writer to Mr. Winston Churchill. (London: privately published, 1948). Kwasniewski, Tadeus, An Open Letter of a Chicago Waiter to Winston Churchill. (Chicago, privately published, 1950), subtitled Let’s Face the Truth, Mr. Churchill. Both writers attacked Churchill’s critique, in The Gathering Storm, of Poland’s participation in the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia.

4 WSC, House of Commons, 16 August 1945, in Richard M. Langworth, ed., Churchill by Himself (New York: Rosetta Books, 2015), 279.

5 William F. Buckley Jr. to the author, quoted in “William F. Buckley: A True Churchillian in the End,” 2020.

6 WSC, Chequers, 21 June 1941, in Langworth, Churchill by Himself, 276.

Further reading

Connor Daniels, “Why Churchill Allied with Stalin,” 2021.

Warren F. Kimball: “Ghost in the Attic: Churchill, the Soviets and the Special Relationship, 2021, in two parts. Part 1 and Part 2.

Richard M. Langworth, “The Maisky Diaries,” edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky,” 2016.

_____ _____, “Facing the Dictator: Stalin, 1946; Hitler, 1938,” 2021.